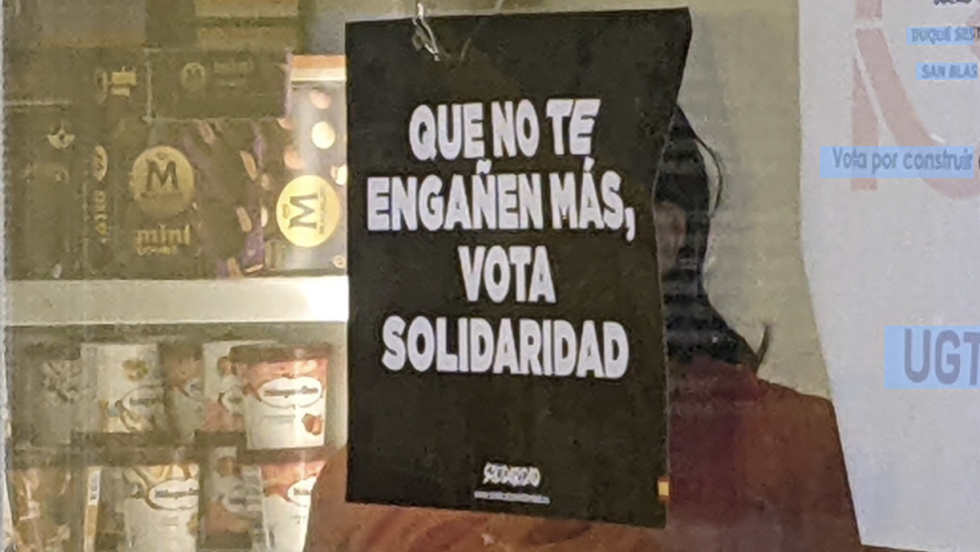

Solidarity sounds like a very positive trait – this is true for English speakers and also in Spain, where solidaridad is prized as the motivator for high rates of blood, organ, gamete, and embryo donation. Early in the pandemic, Spain's national health ministry’s communication strategy to reduce “vaccine resistance” invoked solidarity: “If people understand that by getting their shot they can protect others in a solidary way, it may motivate someone who’s unmotivated.” Solidarity is thus partly understood as a humanitarian orientation to others.

Yet in the arena of international adoption in Spain, which Jessaca Leinaweaver and Barcelona-based colleague Diana Marre have researched for many years, solidarity is a much more contentious and contradictory value. For example, a pamphlet advising Spanish adoption professionals how to evaluate transnational adoption applicants recommends assessing whether a couple “demonstrates capacity to address difficult and demanding situations or conflicts with togetherness and solidarity.” Here, solidarity represents (positive) collaboration and mutual support in a family context. But later in the text, the author warns professionals that one sign of risk is if prospective parents present “motivations for [transnational] adoption that are centered in . . . humanitarianism and/or feelings of solidarity to save a child by removing him/her from his/her country.” Here, solidarity is (negatively) viewed as equivalent to humanitarianism.

These contradictions point to an unresolved tension. Many prospective transnational adoptive parents in Spain express motivations to “help” through adoption, while adoption professionals warn that feelings of solidarity are a sign that adoption would be built on a wrong and unstable foundation. What complicates this even further for anthropologists studying adoption is that family is, in anthropological kinship studies, famously defined (by David M. Schneider in 1968) as consisting of and marked by “enduring, diffuse solidarity.”

In their 2022 article in American Anthropologist, “Solidarity exclusions: Problematizing kinship and humanitarianism from the perspective of transnational adoption,” Leinaweaver and Marre ask, "What is, or should be, the role of solidaridad within the (transnationally adoptive) family?" They conclude that solidaridad’s multivocality within the transnational adoptive family context results in adoptive families being measured by a different standard than nonadoptive families. This reifies a distinction that can potentially harm adoptive families and exclude solidaridad as an active resource for producing kinship. But they also show that solidaridad’s multivocality has broader significance for kinship, both adoptive and nonadoptive, as well as for social and political engagement across inequality.

The co-authors have published several other articles together on related subjects:

- Frekko, Susan, Jessaca Leinaweaver, and Diana Marre. 2015. “How (not) to Talk about Adoption in Spain: On Communicative Vigilance in Spain.” American Ethnologist 42(4): 703–19.

-

Leinaweaver, Jessaca, Diana Marre, and Susan Frekko. 2017. “‘Homework’ and Transnational Adoption Screening in Spain: The Co-Production of Home and Family.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23(3): 562-579.

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca, and Diana Marre. 2022. “Adoption and Fostering.” In The Routledge Handbook of Anthropology and Reproduction, edited by S. Han and C. Tomori, 618–30. Philadelphia, PA: Routledge.